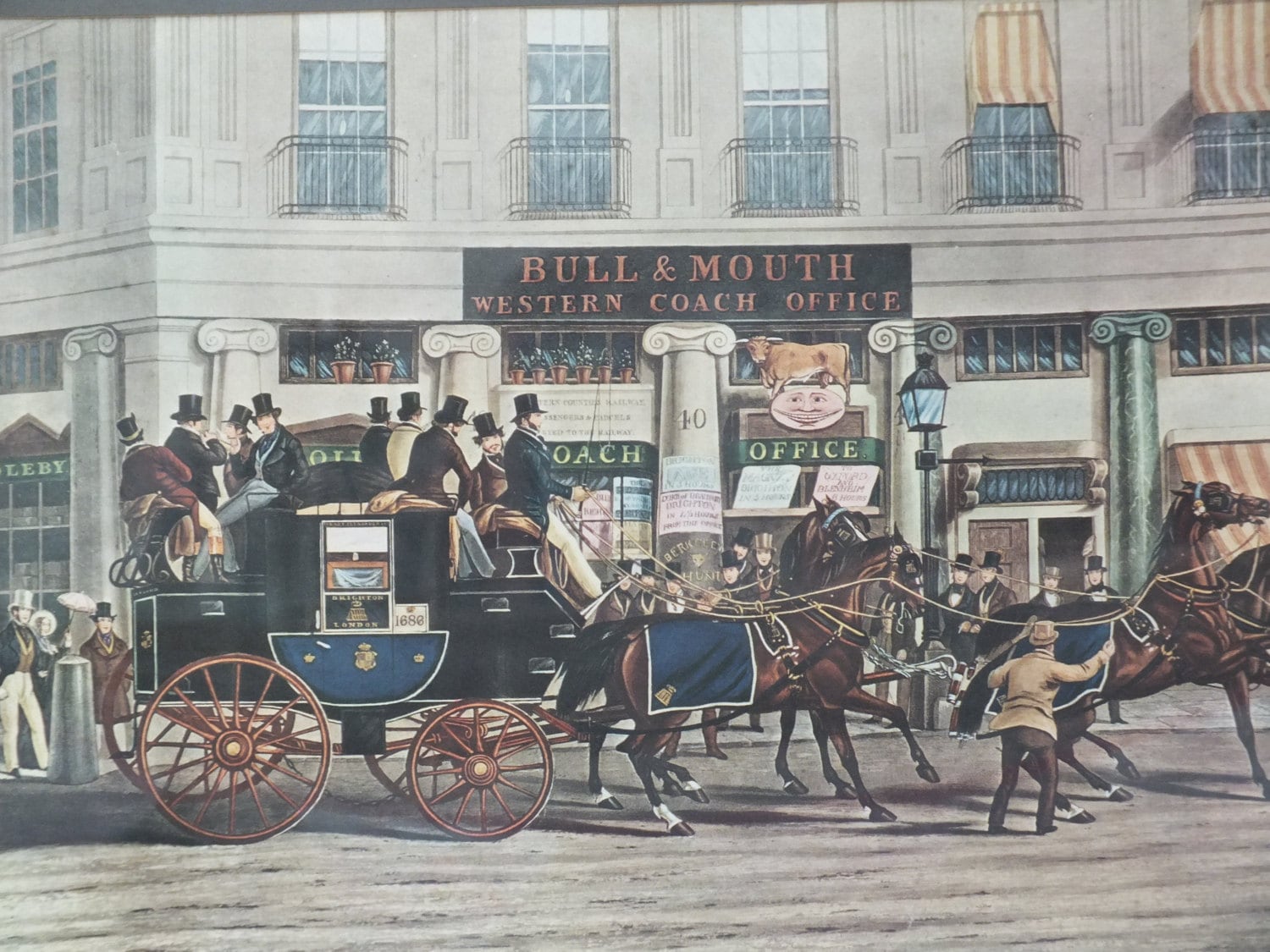

The London to Brighton Royal Mail Stagecoach

outside The Bull and Mouth, Western Coach Office, Lombard Street, London.

Illustration: LILAC COTTAGE WONDERS

Charles Dickens' David Copperfield arrives in London by Stagecoach.

Illustration: THE BRITISH POSTAL MUSEUM AND ARCHIVE

Pip and Estella meet outside The Cross Keys, London.

The Red and Black Royal Mail Stagecoach forms part of the background.

Charles Dickens' Great Expectations.

Illustration: THE BRITISH POSTAL MUSEUM AND ARCHIVE

The Victorian-era Glasgow to London Royal Mail Stagecoach (Number 25).

Illustration: SCOTLAND FOR THE SENSES

The "Tally-Ho".

Hampton Court to Dorking, Surrey, Stagecoach.

Illustration: THE PORTSMOUTH ROAD

The following Text is from THE PORTSMOUTH ROAD

And now, before we proceed further along the Portsmouth Road, we must “change here” for Dorking, a coach-route greatly favoured of late years, both by Mr. Rumney’s “Tally-ho” coach, and Mr. E. Brown’s “Perseverance,” by way of a relief from their accustomed haunts, to St. Albans and elsewhere. The “Perseverance” (which, alas! no longer perseveres) left Northumberland Avenue at eleven a.m., and came down the old route until Surbiton was passed, when it turned off by way of Hook and Telegraph Hill, by Prince’s Coverts to Leatherhead, and so into Dorking.

Mr. Rumney’s “Wonder”—bah! what do I say?—I should say that gentleman’s “Tally-ho” ran to Dorking in 1892, what time the “Perseverance” also ran thither, and a fine seven-and-sixpenny ride it was, there and back. By “there and back” I do not name the route between London and the old Surrey town. Oh no; Mr. Rumney’s was quite an original idea. He gave Londoners the benefit of a country drive throughout, and ran between the sweet rurality of Hampton Court and Dorking. At 11.10 every morning he started from the “Mitre” Hotel, and so, across Hampton Bridge, to Ditton and Claremont, and thence to Dorking . . .

. . . This event brings us to the threshold of the coaching era, for in 1784, four years after the Gordon Riots, mail-coaches were introduced, and the roads were set in order. Years before, when only the slow stages were running, a journey from London to Portsmouth occupied fourteen hours, if the roads were good! Nothing is said of the time consumed on the way in the other contingency; but we may pluck a phrase from a public announcement towards the end of the seventeenth century that seems to hint at dangers and problematical arrivals. “Ye ‘Portsmouth Machine’ sets out from ye Elephant and Castell, and arrives presently by the Grace of[Pg 30] God....” In those days men did well to trust to grace, considering the condition of the roads; but in more recent times coach-proprietors put their trust in their cattle and McAdam, and dropped the piety.

"The New Times".

Guildford, Surrey, Stagecoach.

Illustration: THE PORTSMOUTH ROAD

A fine crowd of coaches left town daily in the ’20’s. The “Portsmouth Regulator” left at eight a.m., and reached Portsmouth at five o’clock in the afternoon; the “Royal Mail” started from the “Angel,” by St. Clement’s, Strand, at a quarter-past seven every evening, calling at the “George and Gate,” Gracechurch Street, at eight, and arriving at the “George,” Portsmouth, at ten minutes past six the following morning; the “Rocket” left the “Belle Sauvage,” Ludgate Hill, every morning at half-past eight, calling at the “White Bear,” Piccadilly, at nine, and arriving (quite the speediest coach of this road) at the “Fountain,” Portsmouth, at half-past five, just in time for tea; while the “Light Post” coach took quite two hours longer on the journey, leaving London at eight in the morning, and only reaching its destination in time for a late dinner at seven p.m.The “Night Post” coach, travelling all night, from seven o’clock to half-past seven the next morning, took an intolerable time; the “Hero,” which started from the “Spread Eagle,” Gracechurch Street, at eight a.m., did better, bringing weary passengers to their destination in ten hours; and the “Portsmouth Telegraph” flew between the “Golden Cross,” Charing Cross, and the “Blue Posts,” Portsmouth, in nine hours and a half.

"The Red Rover".

Guildford to Southampton Stagecoach.

Illustration: THE PORTSMOUTH ROAD

The following Text is from SLEEPING GARDENS

In the early 1800s, when the roads had improved beyond all recognition, travel eventually became ‘almost’ pleasurable. Stagecoaches were able to attain speeds of up to 10 mph – cutting journey times by hours, and, in some cases, by days. What had been a two day journey from London to Cambridge (sixty-one miles) in 1750, was possible in just six hours by 1836.

London pre-dominated as the hub of all Stagecoach services up until the 1750s, but within ten years, Stagecoach services were operating between all major Towns and Cities and the number of provincial links had increased dramatically.

Local services were still served by Carrier’s Carts, generally operating between Public Houses, but the much larger Inns, offering accommodation and fine food, were always the starting and terminating points for those travelling longer distances.

In the 1780s, The Post Coach would take you direct from Stourbridge,

(previously Worcestershire, now West Midlands) to London by Lunchtime the next day.

Illustration: BLACK COUNTRY BUGLE

The return journey commenced in Cambridge at 1.00 in the morning and arrived at “09.00 the same morn”. By 1836, the time had been cut to six hours and one Stagecoach left Cambridge at 10.00 a.m. daily whilst another left London at the same time to travel in the opposite direction.

Ideally there were four Stagecoaches called "The Cambridge Telegraph" – two at each end, one in service, and the other in reserve. In the Late-1700s, it cost £4 a month, including the wages of horse-keepers and stable-hands, to keep a Stagecoach horse on the road. The horses trotted and tried to keep a steady pace of ten miles an hour. Galloping could only be sustained for a short distance and was only indulged in to make up lost time.The lifespan of a horse on a Stagecoach route was only three to four years and they were then sold to farmers for lighter duties.

"The Tantivy".

Stourbridge to Birmingham Stagecoach.

The driver in the picture is Jake Gardner and the Stagecoach stands at its starting point, The Old King's Head, Stourbridge High Street. The Landlord, William Vale, can also be seen, inside the Stagecoach, about to load a large Wicker Basket. The Public House, demolished over a Century ago, stood where Lloyds Bank stands today.

Date: Circa 1860.

Illustration:

Due to the population’s desire to travel, Stagecoach capacity was increased. The maximum number of six passengers (carried in the 1740s) was increased to eight or ten (inside and out) by the end of the Century, and, by 1810, Stagecoaches were large enough to carry up to eight people inside, in ‘reasonable’ comfort, with eight more taking their places outside – open to the elements but at a much reduced fare.

There were accidents though, carrying so many people, as well as their luggage, often led to Stagecoaches tipping over on the more winding roads.

Journeys were also invariably long and tedious and frequent stops were made at Inns along the way. Tired horses would be changed for a fresh team and passengers were allowed ten - twenty minutes for refreshments. For Inn-keepers, the Stagecoaches were a lucrative trade.

A Royal Mail Worcester to London Stagecoach,

decorated in the Black and Scarlet Post Office Livery, 1804.

From The Costume of Great Britain, 1808 (originally issued 1804),

written and engraved by William Henry Pyne (1769-1843).

Author: William Henry Pyne (1769–1843).

(Wikimedia Commons)

Although the Stagecoach era spanned 200 years, the real boom was between 1810 and 1830. During this time a nationwide network of services had been formed and some 3,000 Stagecoaches, and 150,000 horses, both Private and Mail, were employed in the transportation of people.

Freight continued to be carried by the more efficient Canal System until the 1830s, but then went by Railway, as did The Mail from London. It was the arrival of the Railways that put the final nail in the Stagecoach's coffin, for, although they continued to be used in rural areas for some years to come, most people wanted to travel by Railway.

The following Text is from BLACK COUNTRY BUGLE

The photo, above, of "The Tantivy" Stagecoach, probably dates from around 1860, when regular Stagecoach services were in their dying days. Perhaps the unknown photographer wanted to preserve for posterity a vanishing way of life.

"The Tantivy" Stagecoach ran from Stourbridge to Birmingham, departing at 10 a.m. every Monday, Thursday, and Saturday, and called at Cradley, Halesowen and Rowley, en route. One of its Staging Posts, where it took on fresh horses, was at The New Inn, Halesowen, demolished in the 1950s.

Several other Stagecoaches ran from The Old King's Head. In the 1820s, John Jolly ran Stagecoaches from Stourbridge to Dudley, Worcester, and London. Departing on Monday and on Wednesdays, William Cox ran a service to Wolverhampton. In the Mid-1830s, Thomas Wastel ran Stagecoaches to Wolverhampton and Dudley on Tuesdays and Fridays, and Thomas Ward ran a Thursday service to Wolverhampton and Stafford.

Travelling by Stagecoach was arduous and slow. They were often overcrowded, which sometimes led to overturning. Those riding inside the Stagecoach were cramped, while those travelling outside had to cling on for dear life, while soaked and freezing in Winter. At best, the Stagecoaches averaged seven miles an hour, over roads that could be treacherous in places. It was not uncommon for paving stones to be stolen from the roads, while ruts and potholes could be axle-breaking deep; the nursery rhyme "Dr Foster went to Gloucester" was inspired by the poor nature of the roads. Added to that, passengers were required to dismount on steep hills, in order to spare the horses.

The number of Turnpikes grew and by the 1780s Stourbridge folk could take a Stagecoach from The Talbot Hotel to the Crown Inn, Worcester, a journey that took around half a day. On three days in the week, travellers could take The Holyhead to London Post Coach, which passed through Stourbridge, arriving in London for Lunchtime the next day. This cost the princely sum of £1.7s.0d., roughly equivalent to £150 in today's money, or half that if you were prepared to travel on the outside of the Stagecoach, unprotected from the elements.

Stourbridge's last Turnpike Act was passed in 1816 and concerned the road to Bridgnorth. The money generated by the Turnpikes was used to improve the roads in Stourbridge and, in the 1800s, the steepness of Lower High Street was reduced, new Streets in the Town were laid out and a new, wider Bridge over The River Stour was built.

Nigel Perry, in his book "A History of Stourbridge" (2001), writes: "In the 1840s, the Stagecoaches serving Stourbridge had romantic names, such as The British Queen, Red Rover, Erin-go-Bragh, Rocket, Everlasting, Bang-Up, and Greyhound. Journeys could be made directly from Stourbridge to Birmingham, Brierley Hill and Dudley, Wolverhampton, Worcester and Kidderminster, and Bewdley, Tenbury, Leominster and Ludlow. StageCoaches on Birmingham and Worcester routes were owned by Joseph Gardner of Windmill Street. Another Carrier was Joseph Pemberton, who ran Stagecoaches to Birmingham, Bristol, Dudley, Tipton, Worcester, from The Coach and Horses Inn, High Street."

The old Stagecoaches could not compete with the Railways; rendered obsolete, they went out of business. The last Royal Mail Stagecoach service, from London to Norwich, closed in 1846, after which long distance Mail was carried by Railway.

The 1888 Local Government Act dissolved the remaining Turnpike Trusts and placed Main Roads under the care of the newly-created County Councils.

Photographs of the old Stagecoaches are rare, there being a relatively short overlap between the new technology of photography and the old Stagecoaches, but at least one Black Country Stagecoach was preserved for posterity. If you are wondering where the name "Tantivy" came from, it was an old hunting cry given at full gallop.

No comments:

Post a Comment