Text from Wikipedia - the free encyclopædia,

unless stated otherwise.

English: Imperial Abbey of Ottobeuren. The façade of The Basilica, designed by Johann Michael Fischer, has been hailed as the pinnacle of Bavarian Baroque Architecture

Deutsch: Reichskloster Ottobeuren.

Fassade der spätbarocken Basilika in Ottobeuren.

Erbaut von 1737-1766 von Simpert Kramer (bis 1748) und Johann Michael Fischer.

Русский: Оттобойрен.

Photo: 19. Mai 2004 / erste Veröffentlichung in Wikimedia Commons: 11. Juli 2005.

Source: Own work.

Author: Simon Brixel Wbrix

(Wikimedia Commons)

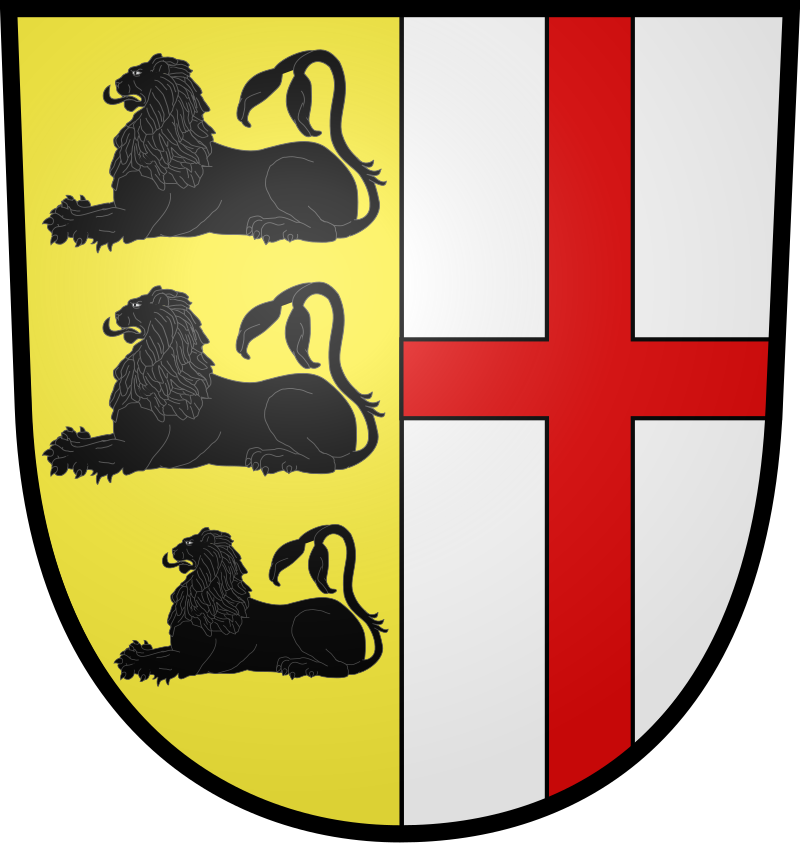

English: Coat-of-Arms of Ottobeuren Abbey.

Deutsch: Wappen Kloster Ottobeuren.

Date: 16 April 2011.

Source:

Author:

Derivative work: OwenBlacker.

(Wikimedia Commons)

The High Altar,

(Kloster Ottobeuren), Bavaria, Germany.

Photo: 18 April 2009.

Source: Own work.

Author: Mattana

(Wikimedia Commons)

Ottobeuren is a Benedictine Abbey, located in Ottobeuren, near Memmingen, in The Bavarian Allgäu, Germany.

For part of its history, Ottobeuren Abbey was one of the forty-or-so, self-ruling, Imperial Abbeys of The Holy Roman Empire, and, as such, was a virtually Independent State.

It was Founded in 764 A.D., by Blessed Toto, and Dedicated to Saint Alexander The Martyr. Of its early history, little is known beyond the fact that Toto, its first Abbot, died about 815 A.D., and that Saint Ulrich was its Abbot in 972 A.D.

In the 11th-Century, its discipline was on the decline, until Abbot Adalhalm (1082–1094) introduced The Hirsau Reform. The same Abbot began a restoration of the decaying buildings, which was completed, along with the addition of a Convent for noble Ladies, by his successor, Abbot Rupert I (1102–1145). Under The Rule of the latter, the newly-founded Marienberg Abbey was recruited with Monks from Ottobeuren Abbey. His successor, Abbot Isengrim (1145–1180), wrote “Annales Minores” and “Annales Majores”.

Blessed Conrad of Ottobeuren was Abbot, from 1193 until his death in 1227, and was described by The Benedictines as a “lover of The Brethren and of The Poor”.

In 1153, and again in 1217, The Abbey was consumed by fire. In the 14th-Century and 15th-Century, it declined so completely that, at the accession of Abbot Johann Schedler (1416–1443), only six or seven Monks were left, and its annual revenues did not exceed forty-six Silver Marks.

Under Abbot Leonard Wiedemann (1508–1546), it again began to flourish: He erected a printing establishment and a Common House of Studies for The Swabian Benedictines. The latter, however, was soon closed, owing to the ravages of The Thirty Years' War.

Ottobeuren became an Imperial Abbey in 1299, but lost this status after The Prince-Bishop of Augsburg had become Vogt of The Abbey. These Rights were renounced after a Court Case at The Reichskammergericht in 1624. In 1710, The Abbey regained its status as an Imperial Abbey, but did not become a Member of The Swabian Circle.

The most flourishing period, in the history of Ottobeuren Abbey, began with the accession of Abbot Rupert Ness (1710–40) and lasted until its secularisation in 1802. From 1711-1725, Abbot Rupert erected the present Monastery, the architectural grandeur of which has merited for it the name of "the Swabian Escorial". In 1737, he also began the building of the present Church, completed by his successor, Anselm Erb, in 1766. In the zenith of its glory, Ottobeuren Abbey fell prey to the greediness of the Bavarian Government. In 1803, Ottobeuren became part of Bavaria. At that time, the Territory had about 12,000 inhabitants and an area of some 165 sq km (64 sq miles).

In 1834, King Louis I of Bavaria restored it as a Benedictine Priory, dependent on Saint Stephen's Abbey, Augsburg. It was granted the status of an Independent Abbey in 1918.

As of 1910, the Community consisted of five Fathers, sixteen Lay Brothers, and one Lay Novice, who had, under their charge, The Parish of Ottobeuren, a District School, and an Industrial School for Poor Boys.

Ottobeuren has been a Member of The Bavarian Congregation of The Benedictine Confederation, since 1893.

Ottobeuren Abbey has one of the richest music programmes in Bavaria, with concerts every Saturday. Most concerts feature one or more of the Abbey's famous organs. The old organ, the masterpiece of French organ-builder, Karl Joseph Riepp (1710–1775), is actually a double organ; it is one of the most treasured historic organs in Europe. It was the main instrument for 200 years, until 1957, when a third organ was added by G. F. Steinmeyer and Co, renovated and augmented in 2002 by Johannes Klais, making 100 stops available on five manuals (or keyboards).

For part of its history, Ottobeuren Abbey was one of the forty-or-so, self-ruling, Imperial Abbeys of The Holy Roman Empire, and, as such, was a virtually Independent State.

It was Founded in 764 A.D., by Blessed Toto, and Dedicated to Saint Alexander The Martyr. Of its early history, little is known beyond the fact that Toto, its first Abbot, died about 815 A.D., and that Saint Ulrich was its Abbot in 972 A.D.

English: The Rococo Interior

Ottobeuren Abbey, Bavaria, Germany.

Español: Basílica, Ottobeuren, Alemania.

Photo: 21 June 2019.

Source: Own work.

Author: Diego Delso (1974–)

(Wikimedia Commons)

Blessed Conrad of Ottobeuren was Abbot, from 1193 until his death in 1227, and was described by The Benedictines as a “lover of The Brethren and of The Poor”.

In 1153, and again in 1217, The Abbey was consumed by fire. In the 14th-Century and 15th-Century, it declined so completely that, at the accession of Abbot Johann Schedler (1416–1443), only six or seven Monks were left, and its annual revenues did not exceed forty-six Silver Marks.

Altar of The Holy Cross,

Ottobeuren Abbey, Bavaria, Germany.

Photo: 17 April 2009.

Source: Own work.

Author: Mattana

(Wikimedia Commons)

Under Abbot Leonard Wiedemann (1508–1546), it again began to flourish: He erected a printing establishment and a Common House of Studies for The Swabian Benedictines. The latter, however, was soon closed, owing to the ravages of The Thirty Years' War.

Ottobeuren became an Imperial Abbey in 1299, but lost this status after The Prince-Bishop of Augsburg had become Vogt of The Abbey. These Rights were renounced after a Court Case at The Reichskammergericht in 1624. In 1710, The Abbey regained its status as an Imperial Abbey, but did not become a Member of The Swabian Circle.

Altar of Saint Benedict and Saint Scholastica

Ottobeuren Abbey, Bavaria, Germany.

Photo: 17 April 2009.

Source: Own work.

Author: Mattana

(Wikimedia Commons)

The Baroque Pulpit,

(Kloster Ottobeuren), Bavaria, Germany.

Photo: 18 April 2009.

Source: Own work.

Author: Mattana

(Wikimedia Commons)

The most flourishing period, in the history of Ottobeuren Abbey, began with the accession of Abbot Rupert Ness (1710–40) and lasted until its secularisation in 1802. From 1711-1725, Abbot Rupert erected the present Monastery, the architectural grandeur of which has merited for it the name of "the Swabian Escorial". In 1737, he also began the building of the present Church, completed by his successor, Anselm Erb, in 1766. In the zenith of its glory, Ottobeuren Abbey fell prey to the greediness of the Bavarian Government. In 1803, Ottobeuren became part of Bavaria. At that time, the Territory had about 12,000 inhabitants and an area of some 165 sq km (64 sq miles).

Basilica of Ottobeuren Abbey.

Photo: 21 May 2007.

Source: Own work.

Author: Dr. Volkmar Rudolf

(Wikimedia Commons)

In 1834, King Louis I of Bavaria restored it as a Benedictine Priory, dependent on Saint Stephen's Abbey, Augsburg. It was granted the status of an Independent Abbey in 1918.

As of 1910, the Community consisted of five Fathers, sixteen Lay Brothers, and one Lay Novice, who had, under their charge, The Parish of Ottobeuren, a District School, and an Industrial School for Poor Boys.

English: The Holy Ghost Organ, Ottobeuren Basilica, Bavaria, Germany.

Deutsch: Chorgestühl mit Heilig-Geist-Orgel (F10), Basilika Ottobeuren.

Photo: 3 March 2009.

Source: Own work.

Author: Johannes Böckh and Thomas Mirtsch.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Ottobeuren has been a Member of The Bavarian Congregation of The Benedictine Confederation, since 1893.

Ottobeuren Abbey has one of the richest music programmes in Bavaria, with concerts every Saturday. Most concerts feature one or more of the Abbey's famous organs. The old organ, the masterpiece of French organ-builder, Karl Joseph Riepp (1710–1775), is actually a double organ; it is one of the most treasured historic organs in Europe. It was the main instrument for 200 years, until 1957, when a third organ was added by G. F. Steinmeyer and Co, renovated and augmented in 2002 by Johannes Klais, making 100 stops available on five manuals (or keyboards).

The Web-Site of Ottobeuren Abbey can be found HERE