A Gentleman’s Wig.

Text and Illustrations: GERI WALTON

It was applied before hair powder, which was also perfumed. Among the popular scents for powder were “musk, civet, ambergris, bergamot, rose, violet, almond, and orange-flower perfumes, and many more of differing qualities.”[8]

Because everyone was wearing a Wig, the price was high. Costs “sometimes amount[ed] to thirty, forty, and fifty guineas … [but] Wigs could be had at all prices, being worn by every class of the community.”[9]

In fact, Wigs were so popular, Wig stealing became a profitable enterprise in England. To accomplish these thefts, a Wig thief, known as “chiving lay” [Editor: A “chiv” is another name for a knife. Hence, the modern slang term “shiv”, for a knife], would position himself “behind Hackney Coaches, which were generally compelled to go at a slow pace owning to the narrowness of the streets and the absence of proper paving, and [the chiving lay] would cut out the back and snatch a gentleman’s Wig from his head … ladies lost their head-dresses [similarly, and] … sometimes a gentleman would find himself suddenly denuded of his head covering in the street.”[10]

It seems, small boys were also trained to be Wig thieves: They would hide in baskets and snatch Wigs off people’s heads as they passed by.

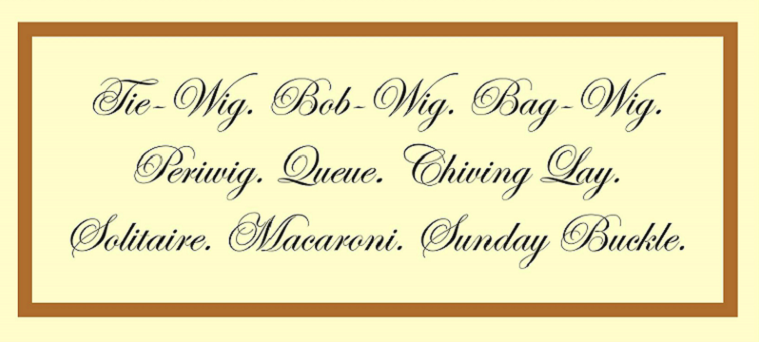

Early engraving of Wigs from 1773.

Public domain.

Because everyone was wearing a Wig, the price was high. Costs “sometimes amount[ed] to thirty, forty, and fifty guineas … [but] Wigs could be had at all prices, being worn by every class of the community.”[9]

In fact, Wigs were so popular, Wig stealing became a profitable enterprise in England. To accomplish these thefts, a Wig thief, known as “chiving lay” [Editor: A “chiv” is another name for a knife. Hence, the modern slang term “shiv”, for a knife], would position himself “behind Hackney Coaches, which were generally compelled to go at a slow pace owning to the narrowness of the streets and the absence of proper paving, and [the chiving lay] would cut out the back and snatch a gentleman’s Wig from his head … ladies lost their head-dresses [similarly, and] … sometimes a gentleman would find himself suddenly denuded of his head covering in the street.”[10]

It seems, small boys were also trained to be Wig thieves: They would hide in baskets and snatch Wigs off people’s heads as they passed by.

Various Wigs remained popular throughout the 1700s, and almost every profession had their own peculiar Wig, with “the oddest appellations … given to them.”[11]

Alice More Earle noted that each profession seemed to chose a Periwig that best expressed its function. For instance,

“The caricatures of the period represent[ed by] full-fledged lawyers with a towering frontlet and a long bag at the back tied in the middle; while students of the university … [sported] a Wig flat on the top, to accommodate their stiff cornered hats, and a great bag like a lawyer’s at the back.”[12]

Yet, for all the Wig’s popularity, the French Revolution and England’s 1795 hair powder tax — an annual tax costing one guinea and imposed under William Pitt — put an end to Wig wearing.

French revolutionaries revolted against anything that reminded them of nobility or the Monarchy, and, in England, when the tax was enacted, Whig leaders were said to have cut off their “queues”, thereby heralding in the Wigless and natural hairstyles embraced during the French Directory and Regency era.

References:[1] Hill, Georgiana, A History of English Dress from the Saxon Period to the Present Day, Vol. 2, 1893, p. 9.

[2] Sydney, William Connor, England and the English in the Eighteenth Century, Vol. 1, 1892, p. 106.

[3] Hill, Georgiana, p. 18.

[4] Ibid, p. 19.

[5] Ibid., p. 25.

[6] Ibid., p. 20.

[7] Ibid., p. 12.

[8] Ibid., p. 13.

[9] Ibid., p. 22.

[10] Ibid., p. 22-23

[11] Ibid., p. 19.

[12] Earle, Alice Morse, Two Centuries of Costume in America, Volume 1, 1903 p. 336-337.